SSK focuses on experiential architecture that integrates the form and meaning inherent in space by utilizing data and systems. SSK implements adaptive architecture, an active methodology that transcends the physical limitations of space and ensures a healthy living environment through the optimal balance of form and function. It aims to revitalize fragmented daily life through refined spatialization of intangible elements that affect spatial psychology, such as light, shadow, sound, and fluid dynamics. As a high-end studio that performs comprehensive design from furniture and lighting, which are the basic units of architecture, to detailed design and supervision, SSK does not accept low-cost projects or meaningless prolific works. As a design-oriented studio that pursues the pinnacle of architectural detail through dense study, SSK continues to work on innovative spaces.

SSK 는 공간에 담긴 조형과 의미를 데이터와 시스템에 기반하여 통합하는 실증적인 건축을 추구합니다. 형상과 기능의 최적화된 균형을 통해 공간이 지닌 물리적 한계를 극복하고 건강한 정주환경을 보장하는 능동적인 건축방법론인 Adaptive Architecture (환경적응건축)을 지향합니다. 이는 공간심리에 영향을 미치는 빛, 음영, 소리, 유체 등 무형요소의 정제된 공간화를 통해 파편화된 일상을 재생하는데 목적이 있습니다. 건축의 기본단위인 가구와 라이팅부터 실시설계 및 공사감리까지 종합디자인을 수행하는 High-end Studio 로 저가수주 및 무의미한 다작은 하지 않습니다. 밀도있는 스터디를 통해 건축 디테일의 정점을 추구하는 Design-oriented Studio 로 혁신적인 공간작업을 이어가고 있습니다.

What is good architecture? What standards define it? Can it endure forever? There are no definitive answers. Yet one thing is clear: the belief that only architects are entitled to engage with space is a fallacy. The arrangement of objects in a shop window, the constant flow of cars filling and emptying a road, the row of houses along an alley lighting up one by one as evening settles in, the street vendors’ carts lining the pavements—these, too, are masters of spatial practice. Their architecture is modest, honest, and unpretentious. It shows us that architecture should not merely contain and support human life, but extend further, acting as a conduit through which countless stories of living can pass. A dirty piece of cheese discarded in an alley becomes a precious resource for ants. Drawn by its pungent scent, they gather, and the cheese is transformed into a bustling street, a square, a marketplace. Good architecture ought to resemble a well-aged cheese. It should assert itself even in polluted or neglected places, breathing new life into them. My small room of just 33㎡ can be considered good architecture because it causes no discomfort. Laundry dries easily. The space is neither too cold nor too hot. Hot water flows freely from the tap. When the windows are opened, a gentle breeze ventilates the room, and sunlight reaches every corner. A bookshelf by the door shields the room from the clatter of shoes in the corridor outside. Good architecture must be distinguished from architecture that is merely pleasing to look at. It does not arise from the latest fashions circulating within architectural circles, but from the lives of ordinary people. Architecture born of an architect’s vanity or of transient trends serves only a chosen few. It is not a piece of cheese shared by all, but a private indulgence. True architecture does not emerge from images on a screen, celebrated by architects as “creations,” but from the smell of cooking, the sound of singing, and the murmur of televisions—elements that together weave the narratives of everyday life. A good architect must understand how to allow this cheese called architecture to mature: to refine its usefulness, to deepen its capacity, and to make room for new stories yet to unfold.

좋은 건축이란 무엇인가. 어떤 기준이 그것을 정의하는가. 과연 영원히 지속될 수 있는가. 이에 대한 명확한 답은 존재하지 않는다. 그러나 한 가지는 분명하다. 공간을 다룰 권리가 오직 건축가에게만 있다는 생각은 오류다. 쇼윈도에 진열된 물건들의 배치, 끊임없이 도로를 채웠다 비워내는 자동차의 흐름, 저녁이 되면 골목을 따라 하나둘씩 켜지는 주택의 불빛, 인도를 점유한 노점상의 수레들 역시 공간을 능숙하게 다루는 행위다. 이들은 소박하고 정직하며 꾸밈이 없다. 이러한 사례들은 건축이 단순히 인간의 삶을 담고 지탱하는 틀에 머무는 것이 아니라, 수많은 삶의 이야기가 오가는 통로가 되어야 함을 보여준다. 골목에 버려진 더러운 치즈 조각은 개미들에게 귀중한 자원이 된다. 특유의 냄새에 이끌려 개미들이 모여들고, 치즈는 어느새 분주한 거리이자 광장, 하나의 시장으로 변모한다. 좋은 건축은 이처럼 잘 숙성된 치즈와 같아야 한다. 오염되고 방치된 장소에서도 스스로의 존재를 드러내며, 공간에 새로운 생명을 불어넣어야 한다. 고작 33㎡에 불과한 나의 작은 방은 불편함이 없다는 이유만으로도 훌륭한 건축이라 할 수 있다. 빨래는 쉽게 마르고, 공간은 지나치게 춥지도 덥지도 않다. 수도꼭지에서는 뜨거운 물이 끊임없이 흐르고, 창문을 열면 부드러운 바람이 방을 환기시키며 햇빛이 구석구석 스며든다. 문 옆에 놓인 책장은 복도에서 울리는 신발 소리를 자연스럽게 차단한다. 훌륭한 건축은 단순히 보기 좋은 건축과 구별되어야 한다. 그것은 건축계 내부에서 소비되는 최신 유행에서 비롯되는 것이 아니라, 평범한 사람들의 삶에서 출발한다. 건축가의 허영이나 일시적인 트렌드에서 탄생한 건축은 소수의 선택된 이들을 위한 것일 뿐이다. 모두가 함께 나눌 수 있는 치즈가 아니라, 개인적 욕망을 충족시키는 사치품에 가깝다. 진정한 건축은 건축가들이 화면 속 이미지에 ‘창조’라는 이름을 붙이며 찬미하는 결과물에서 비롯되지 않는다. 그것은 요리 냄새와 노랫소리, 텔레비전의 웅성거림처럼 일상의 감각들이 겹겹이 쌓이며 만들어내는 삶의 이야기 속에서 태어난다. 훌륭한 건축가는 건축이라는 치즈가 어떻게 숙성되어야 하는지를 이해해야 한다. 다시 말해, 건축의 효용을 다듬고 그 가능성을 심화시키며, 아직 펼쳐지지 않은 새로운 이야기들이 스며들 수 있는 여지를 마련해야 한다.

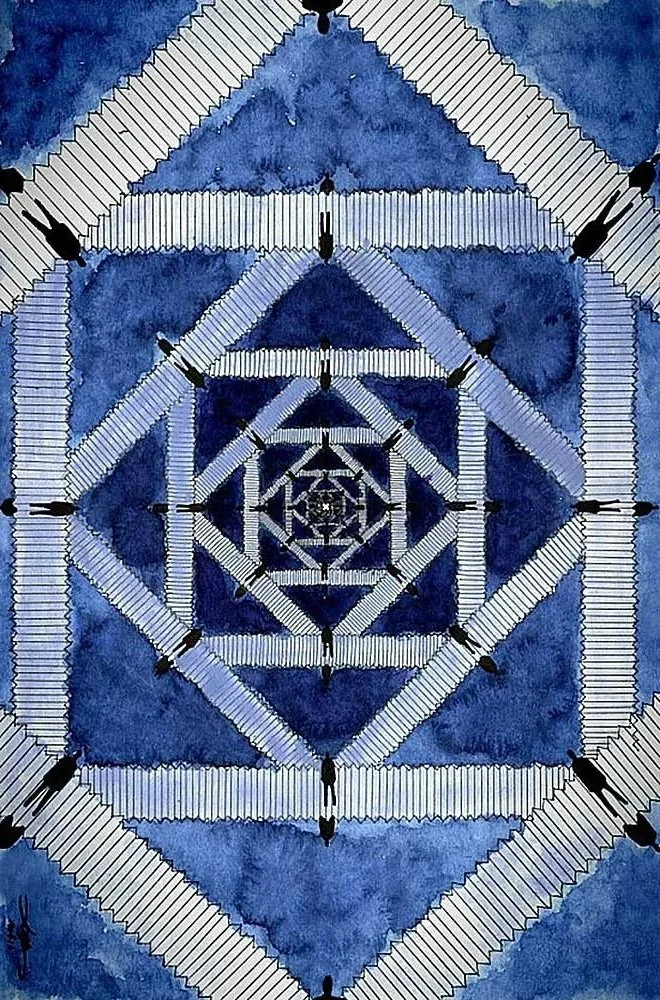

AU MAGASIN DE NOUVEAUTES (육면각체의 재해석) / Korea Painting / WxL : 387x270mm / Sooseok L. Kim (2008)

SIMULACRE / Korea Painting / WxL : 210x230mm / Sooseok L. Kim (2011)

Architecture that is as universally appropriate as a piece of cheese—recognisable and acceptable to anyone—is an ideal to which every architect aspires. Yet the difficulty that repeatedly emerges in the pursuit of such an ideal lies in the act of judgement itself: selecting the most appropriate solution from a multitude of ideas and alternatives. During this process, ideas that once appeared lucid and convincing often reveal themselves, once articulated, to be little more than naïve assumptions. When I attempt to explain or discuss the difficulties of my work with others, I often find myself lamenting that an unfinished work can seem more appropriate than a completed one. At such moments, I begin to question whether I am merely going through the motions of making art. This doubt is amplified by the misconception that great artists produce only works underpinned by flawless and irrefutable logic. Yet X-ray analyses of celebrated paintings reveal countless traces of revision and correction, and Renaissance masters, aided by the camera obscura, exaggerated expressive details through repeated adjustment and refinement. These acts of trial and error were not anomalies but entirely natural stages of the creative process. Still, my longing for a perfect mode of creation often leads me to disparage myself as nothing more than an ordinary student of art. Ideas that feel unassailable in my own mind turn into childish complaints the moment they are spoken aloud. There are, of course, occasions when a peak is reached without such trial and error. Viewed in contrast to the laborious struggles of others, such moments can foster pride and even arrogance. Yet works completed without encountering error often result in a different kind of failure—a consequence of insufficient preparation. When art is understood as an act of creation grounded in a motif shaped by personal sensibility, all creative acts become expressions filtered through the self, regardless of whether their maker consciously labels them as art. To create, then, is to express oneself. Art becomes inseparable from the self, and with this comes the responsibility of producing something capable of touching and moving others. This responsibility is also the source of the artist’s pride. So long as one’s thoughts and works are subject to the judgment of others—so long as they are required to justify both the artist and the work—no one willingly accepts ridicule born of careless or inadequate outcomes. In this sense, the difficulties inherent in the architectural process, in the pursuit of what is most ‘appropriate’, resemble the growing pains of the architect. I, too, have experienced the despair of seeing a compelling idea reduced to banality when expressed externally, yet this is neither exceptional nor tragic—it is simply part of the ordinary process. Creating work that is truly appropriate through repeated trial and error is both the burden the artist must bear and the fundamental ambition that drives them.

누구나 알아보고 받아들일 수 있는, 마치 치즈 한 조각처럼 보편적으로 적합한 건축은 모든 건축가가 열망하는 이상이다. 그러나 이러한 이상을 향한 과정에서 끊임없이 마주하게 되는 어려움은 판단의 문제, 즉 수많은 아이디어와 대안 가운데 가장 적절한 해법을 선택하는 행위에 있다. 이 과정에서 한때 명확하고 설득력 있어 보였던 생각들은, 막상 언어로 옮겨지는 순간 순진한 가정에 불과했음을 드러낸다. 작업의 어려움을 타인에게 설명하거나 논의하려 할 때면, 완성된 결과보다 미완의 상태가 더 적절해 보이는 현실에 종종 좌절하게 된다. 그때마다 나는 과연 내가 예술을 만드는 행위 자체에만 매몰되어 있는 것은 아닌지 스스로에게 묻게 된다. 위대한 예술가란 오직 흠잡을 데 없고 반박 불가능한 논리에 의해 완성된 작품만을 남긴다는 통념은 이러한 의심을 더욱 증폭시킨다. 그러나 유명 회화 작품을 X-ray로 들여다보면 수많은 수정과 보완의 흔적이 발견되며, 르네상스 시대의 거장들 역시 'Camera Obscura'의 도움을 받아 반복적인 조정과 다듬기를 통해 표현적 밀도를 축적해 왔다. 이러한 시행착오는 예외적인 사건이 아니라 창작 과정에 내재된 지극히 자연스러운 단계였다. 그럼에도 불구하고 완벽한 창작 방식을 갈망하는 나는 종종 스스로를 평범한 미술의 학습자에 불과하다고 평가절하한다. 머릿속에서는 결점 없이 완결된 듯 보이던 생각들이, 입 밖으로 나오는 순간 유치한 불평으로 전락하기도 한다. 물론 시행착오 없이 정점에 이르는 순간도 존재한다. 그러나 타인의 고된 과정과 대비될 때 이러한 순간은 자부심을 넘어 오만으로 비치기 쉽다. 더 나아가, 오류 없이 완성된 작업은 종종 또 다른 형태의 실패, 즉 충분한 준비 없이 도달한 결과로 귀결되기도 한다. 예술을 개인의 감수성에 의해 형성된 모티프를 바탕으로 한 창조 행위로 이해한다면, 모든 창작은 그것을 예술로 인식하든 그렇지 않든 창작자의 자아를 통과한 표현일 수밖에 없다. 창조는 곧 자기표현이며, 예술은 자아와 분리될 수 없는 존재가 된다. 이로부터 타인의 감각과 감정을 움직일 수 있는 무언가를 만들어야 한다는 책임이 발생하며, 이러한 책임감은 동시에 예술가가 지닐 수 있는 자긍심의 근원이 된다. 사유와 작업이 타인의 평가를 통해 의미를 부여받고, 예술가와 작품 모두가 그 평가 앞에서 정당성을 획득해야 하는 한, 누구도 부주의하거나 미흡한 결과로 인해 조롱받기를 원하지 않는다. 이러한 맥락에서 가장 ‘적절한’ 상태를 향해 나아가는 건축의 과정은 건축가의 성장통과 다르지 않다. 나 역시 훌륭하다고 믿었던 아이디어가 외부로 표현되는 순간 진부하게 느껴지는 절망을 경험해 왔지만, 이는 특별하거나 비극적인 사건이 아니라 창작 과정에 내재된 일상적인 국면일 뿐이다. 반복되는 시행착오를 통해 비로소 적절한 작품에 도달하는 일은 예술가가 감내해야 할 짐이자, 동시에 그들을 끊임없이 움직이게 하는 근본적인 열망이다.

The traditional architectural paradigm—defining space through floors, walls, ceilings, and columns—is undergoing a profound transformation. At the centre of this shift stands the user. In recent years, as bold and experimental designs have been realised as actual spaces through digital tools, users have begun to demand ever more diverse and novel spatial experiences from architects. Where revolutions in architectural design were once driven primarily by the pursuit of new materials—progressing from wood to stone, from concrete to steel and glass—today the evolution of architecture is increasingly propelled by the public’s desire for new kinds of space. This shift stems in part from architecture’s inherent constraint: the long span of time required for its realisation. Yet advances in materials and construction technologies have also positioned architecture as a potential leader in broader social change. As a result, the creation of new spatial concepts has become a more urgent and significant task than the invention of radically new materials. The notion of the ‘box’ is no longer limited to a six-sided object defined by edges and corners, but has expanded into a more abstract understanding: an entity that contains and produces space. In other words, the liberation of architectural paradigms—made possible by new materials and evolving spatial perceptions—now demands from architects a level of both innovation and responsibility unprecedented in earlier eras. Ultimately, the architect is released from the obligation to produce standardised, box-like forms dictated by uniformity and is instead granted the freedom to think, interpret, and express space in more open and imaginative ways.

바닥, 벽, 천장, 기둥으로 공간을 규정해 온 전통적 건축 패러다임은 지금 근본적인 전환기를 맞고 있다. 이 변화의 중심에는 사용자가 있다. 최근 디지털 도구의 발전으로 대담하고 실험적인 디자인이 실제 공간으로 구현되면서, 사용자들은 건축가에게 이전보다 훨씬 새롭고 다층적인 공간 경험을 요구하고 있다. 과거 건축 디자인의 혁신은 주로 재료의 발전에 의해 주도되었다. 목재에서 석재로, 콘크리트에서 철강과 유리로 이어진 재료의 변화는 곧 건축의 진화를 의미했다. 그러나 오늘날 건축의 진화는 더 이상 재료 자체가 아니라, 새로운 유형의 공간에 대한 대중의 요구에 의해 촉발되고 있다. 이는 건축이 본질적으로 장기간의 시간과 투자를 필요로 하는 분야라는 한계에서 비롯된 변화이기도 하다. 한편, 재료 기술과 건설 방식의 발전은 건축을 단순한 결과물이 아닌, 사회적 변화를 이끌 수 있는 잠재적 주체로 자리매김하게 했다. 그 결과, 근본적으로 새로운 재료를 발명하는 일보다 새로운 공간 개념을 창출하는 일이 더욱 시급하고 중요한 과제로 떠올랐다. 이와 함께 ‘박스’에 대한 개념 역시 변화하고 있다. 박스는 더 이상 모서리와 면으로 규정되는 육면체가 아니라, 공간을 담고 생성하는 추상적 실체로 인식된다. 새로운 재료와 확장된 공간 인식이 가능하게 한 이러한 패러다임의 해방은 이제 건축가에게 이전 어느 시대보다 큰 혁신성과 책임을 동시에 요구한다. 궁극적으로 건축가는 획일성과 표준화가 강요한 상자형 건축을 반복적으로 생산해야 하는 의무에서 벗어나, 보다 자유롭고 개방적인 태도로 공간을 사유하고 해석하며 표현할 수 있는 가능성을 획득하게 되었다.

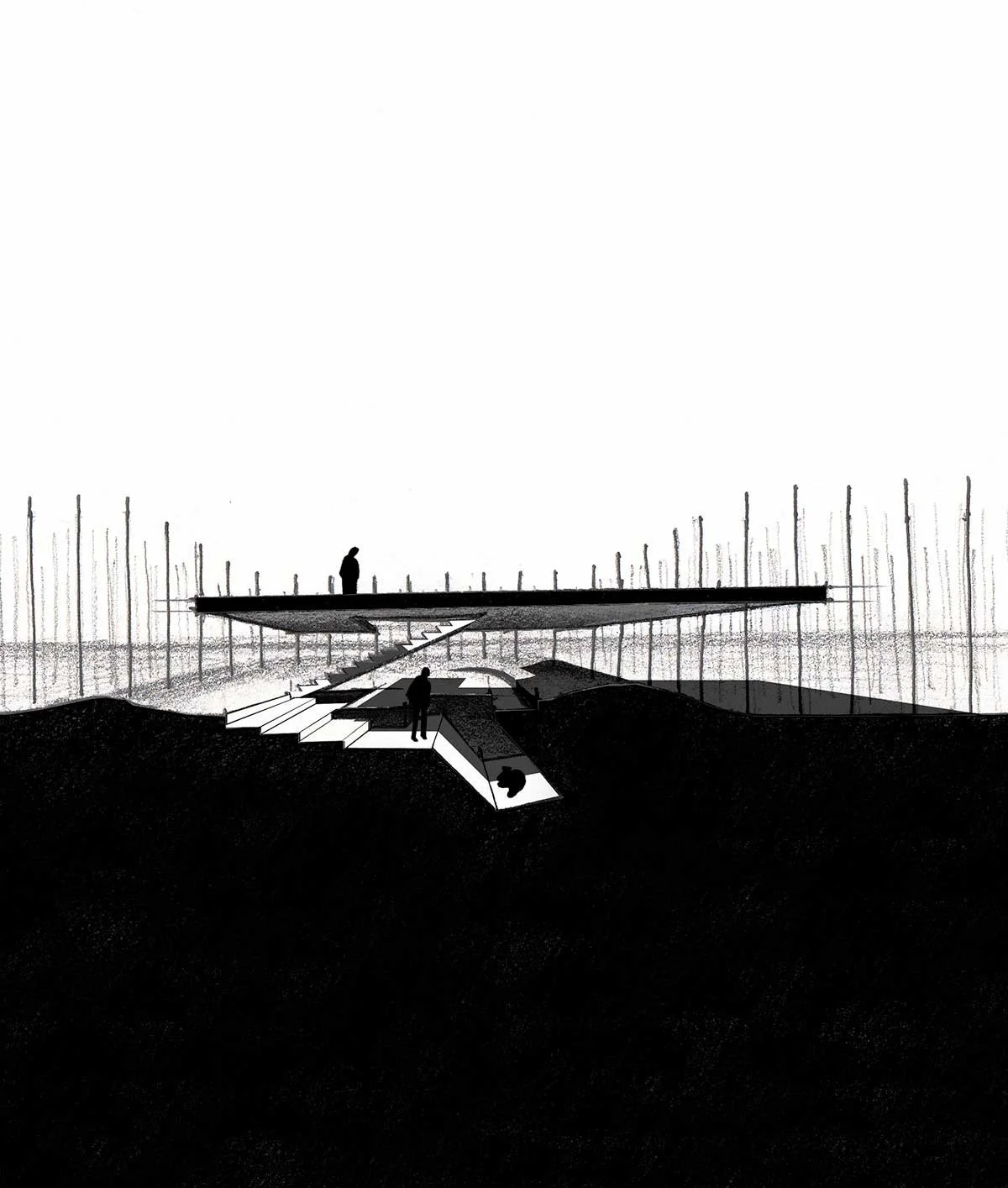

Floating Illusion / Pen / WxL : 300x400mm / Sooseok L. Kim (2013)

Tomb / Pen / WxL : 400x300mm / Sooseok L. Kim (2013)

Beyond the production of visually spectacular architectural forms lies a deeper consideration of the architect’s potential role. In this sense, Bruce Branit’s video serves as a cautionary message to contemporary architects who have lost sight of their social responsibility by focusing exclusively on architecture’s visual expression. What is most essential—yet often the first to be sacrificed in the name of efficiency and commercial logic—is the architect’s willingness to explore new possibilities and to act as a conduit for human life. What, then, has become of the architect’s mind when it is guided solely by the demands of service? Seen in this light, the works of masters such as Louis I. Kahn, Peter Zumthor, and Tadao Ando take on particular significance. Through traditional yet experimental approaches to light and space, they pioneered expanded roles for the architect beyond mere form-making. Spaces that possess the power to move people are not created through efficient programmes or radical designs alone, but emerge from the stories that are generated, layered, and connected within them. To consider how such stories come into being, and how they are conveyed through space, is to move closer to what may be called ‘appropriate’ architecture.

시각적으로 화려한 건축 형태를 생산하는 일 너머에는 건축가의 잠재적 역할에 대한 보다 근본적인 성찰이 존재한다. 이러한 맥락에서 브루스 브래닛의 영상은 건축의 시각적 표현에만 몰두한 채 사회적 책임을 망각한 현대 건축가들에게 던지는 경고로 읽힌다. 효율성과 상업적 논리라는 이름 아래 가장 먼저 배제되는 것은, 역설적으로 가장 본질적인 요소인 새로운 가능성을 탐구하려는 건축가의 태도이며, 인간의 삶을 잇는 통로로서 건축을 사유하려는 의지다. 오직 ‘서비스’라는 요구에만 반응하도록 길들여진 건축가의 정신은 과연 어떤 상태에 놓여 있는가. 이러한 질문 속에서 Louis I. Kahn, Peter Zumthor, Tadao Ando와 같은 거장들의 작업은 특별한 의미를 획득한다. 이들은 빛과 공간이라는 전통적이면서도 근원적인 요소를 실험적으로 다루며, 단순한 형태 생산을 넘어 건축가의 역할 자체를 확장해 왔다. 사람의 감각과 감정을 움직이는 공간은 효율적인 프로그램이나 혁신적인 디자인만으로 완성되지 않는다. 그러한 공간은 그 안에서 생성되고, 축적되며, 서로 연결되는 이야기들로부터 형성된다. 이 이야기들이 어떻게 발생하고, 공간을 매개로 어떻게 전달되는지를 사유하는 일은 ‘적절한’ 건축이라 부를 수 있는 지점에 한층 더 가까이 다가가는 과정이다.

Architecture of the future will pursue an even greater degree of freedom, both in form and in function, building upon the conditions of the present. Yet even within this new paradigm, architecture’s role as a channel or medium must not be overlooked. Great architecture is not defined solely by historical value or formal excellence. Its true significance lies, as discussed earlier, in its capacity for communication. Architecture is simultaneously the most expensive artefact humanity can possess and one of its most powerful means of communication. Regardless of programme or use, architecture has always served as a stage for discourse and conflict throughout history—outcomes born of communication. For this reason, good architecture must fulfil its role as an intermediary. Much like Leonardo da Vinci’s sfumato, in which subtle transitions between colours dissolve the boundaries of form, architecture too must function as a catalyst that softens borders and weaves together diverse narratives within a given context. A compelling example of this can be found in the ‘Middle Architecture’ that is rapidly emerging across major Asian cities. This high-density typology integrates residential, commercial, and business functions within four- to five-storey buildings, encouraging interaction among people of different professions and fostering new forms of urban culture. In essence, Middle Architecture represents a new architectural paradigm in which users coexist by subdividing dense spatial conditions in high-rent urban areas. It is a distinctive residential form that emerged organically as a means of survival. Many architects are proposing and realising such architecture in cities in a guerrilla-like manner. Because this model cannot exist without dialogue and mutual understanding among neighbours, areas in which Middle Architecture takes root often experience improvements in living conditions, including safety and sanitation. This makes it a particularly viable response to future urban development in Asia, where rapid growth and high population density exceed those of European and North American cities. In this sense, the future of architecture will not be limited to the pursuit of radical new designs. Beyond design itself, the creation of new spatial cultures and their introduction into everyday life will become an essential part of architectural practice. Architects must therefore consider how design can function effectively as an intermediary, and how it may be accepted and sustained by its users. The ‘appropriate’ spaces to which architects aspire will be those that generate new cultures of living, spreading organically through their users—much like colours that dissolve and merge in a mist, as in sfumare. This is by no means an easy task. The new generation of architects, to which I belong, bears the responsibility of moving beyond form-making to create living spaces capable of containing the stories of those who inhabit them. This responsibility aligns with traditional architectural values that regard architecture as something that must remain constantly alive. It is this conviction that will continue to drive architects forward. In the end, architects become architects once again.

미래의 건축은 현시대의 조건을 바탕으로 형태와 기능 양 측면에서 더욱 큰 자유를 추구할 것이다. 그러나 이러한 새로운 패러다임 속에서도 건축이 소통의 통로이자 매개체로서 수행해 온 역할은 결코 간과되어서는 안 된다. 훌륭한 건축은 단순히 역사적 가치나 형식적 완성도로만 정의되지 않는다. 앞서 살펴보았듯, 건축의 본질적 의미는 소통의 능력에 있다. 건축은 인류가 소유할 수 있는 가장 값비싼 산물인 동시에 가장 강력한 소통 수단 중 하나다. 용도나 기능과 무관하게, 건축은 역사 전반에 걸쳐 담론과 갈등이 발생하는 장으로 작동해 왔다. 이러한 현상은 모두 소통의 결과다. 따라서 좋은 건축은 매개체로서의 역할을 충실히 수행해야 한다. 레오나르도 다빈치의 스푸마토 기법이 미묘한 색채의 전이를 통해 형태의 경계를 허물듯, 건축 또한 주어진 맥락 속에서 경계를 완화하고 다양한 이야기를 엮어내는 촉매로 기능해야 한다. 이러한 가능성을 보여주는 대표적인 사례가 아시아 주요 도시에서 빠르게 확산되고 있는 ‘중간 건축(Middle Architecture)’이다. 이 고밀도 건축 유형은 4~5층 규모의 건물 안에 주거, 상업, 업무 기능을 복합적으로 수용함으로써, 다양한 직업과 삶의 방식을 지닌 사람들이 자연스럽게 교류하도록 유도하고 새로운 도시 문화를 형성한다. 중간 건축은 임대료가 높은 도심에서 밀집된 공간을 세분화해 사용자들이 공존하는 방식을 제시하는 새로운 건축 패러다임이다. 이는 생존 전략으로서 자발적으로 발생한 독특한 주거 형태이기도 하다. 많은 건축가들이 도시 곳곳에서 이러한 건축을 일종의 게릴라적 방식으로 제안하고 실현하고 있다. 이 유형은 이웃 간의 소통과 상호 이해 없이는 성립할 수 없기에, 중간 건축이 정착한 지역에서는 안전과 위생을 포함한 생활 환경 전반이 개선되는 경우가 많다. 이러한 특성은 급속한 성장과 높은 인구 밀도를 겪고 있는 아시아 도시들의 미래 개발에 있어 중간 건축이 효과적인 대안이 될 수 있음을 보여준다. 이처럼 건축의 미래는 혁신적인 형태나 급진적인 디자인을 추구하는 데에만 머물지 않는다. 디자인을 넘어 새로운 공간 문화를 창출하고, 이를 일상 속에 스며들게 하는 일 또한 건축의 핵심 과제가 된다. 따라서 건축가는 디자인이 어떻게 매개체로 작동할 수 있는지, 그리고 그것이 사용자들에게 어떻게 받아들여지고 지속될 수 있는지를 고민해야 한다. 건축가가 지향하는 ‘적절한’ 공간이란, 'Sfumare'처럼 안개 속에서 색채가 서로 스며들며 확산되듯, 사용자들을 통해 자연스럽게 퍼져나가는 새로운 삶의 문화를 담아내는 공간이다. 이는 결코 쉬운 과제가 아니다. 내가 속한 새로운 세대의 건축가들은 형태를 만드는 데 그치지 않고, 그 안에서 살아가는 사람들의 이야기를 담아낼 수 있는 공간을 만들어야 할 책임을 지닌다. 이러한 책임은 건축을 끊임없이 살아 있는 존재로 인식해 온 전통적인 건축적 가치와 맞닿아 있다. 바로 이 신념이 앞으로의 건축을 이끄는 동력이 될 것이다. 결국 건축가는 다시, 건축가가 된다.

Mediator / Render / Sooseok L. Kim (2013)